Pixar and the Myth of the Cornered Resource

Why individual talent is inevitably overrated and overindexed—even in creative fields.

Let’s start with our supervillain: the wicked nerd-inventor Syndrome. A would-be superhero rejected by The Incredibles in their prime, Syndrome has vowed revenge. World destruction, perhaps? The slow psychological subordination of the masses to his iron grip? Well, no, not quite. Syndrome has something else in mind. He wants nothing less than to… democratize superpowers by sharing his tools and technology with the world.

At the heart of Pixar’s The Incredibles lies a fantastical proposition: not that superheroes’ real disguise is in impersonating our suburban-sitcom neighbors, but that technology itself is villainous because it can let us all be superheroes. Seen two decades later, The Incredibles’ story—superheroes unleashing their powers to fight state regulation and a copycat rival—can seem a bit like a Silicon Valley bromide, or even an Apple allegory, instructing us to Be Special and Think Different in service of giving power to centralized powers. But strangely, if you tell the story of The Incredibles through its villain rather than hero, you might also get a Silicon Valley Hero’s Journey. “When everyone is special, no one is,” brays Syndrome in a line that will sound especially supervillaneous for anyone who has lived in deadly fear of… democracy? Equal opportunity? Growth Mindsets? (Alas, The Incredibles is sadly silent on the Venture Capitalists who presumably await terrific returns on Syndrome’s superhero-as-a-service innovations.)

There are a couple ways we might understand The Incredibles’ ode to Genetic Superiority vanquishing the doomsday threat of Empowering Technology. One is simply to note that the movie itself, developed in the early 2000s with then-novel tools for rendering humans in 3D animation, is very much fueled by its own anxiety towards its mass audience and its own technology. If you like, you could see The Incredibles as an uneasy expression of society’s increasingly confused allegiance to both Creative Geniuses and Democratizing Technology, embodied simultaneously by figures like Pixar’s CEO Steve Jobs as well as Pixar’s own dual mandate to be both a Hollywood Studio and Silicon Valley Tech Company.

But that anxiety and unease are hardly uncommon to superhero movies. The recent spate of Marvel villains and demi-villains—Mysterio, Wanda, Loki—all serve as stand-ins for the filmmakers themselves, for example, creatives who write and direct entire worlds for other characters to inhabit. What’s unique about The Incredibles is that it sees technology as dangerous not for how it manipulates us, but for how it can be shared and used by all of us. The real danger, for The Incredibles, is that technology can socialize, share, and decentralize individual superpowers.

And in that light, we might understand The Incredibles in another way—as the rare movie that articulates The Myth of the Cornered Resource. Popularized by Hamilton Helmer’s wonderful 7 Powers as one of seven competitive business advantages, the “cornered resource” refers to “a coveted asset” to which a business has ongoing and proprietary access and which will drive differential returns. Helmer’s case study for cornered resources is, in fact, Pixar itself, whose “braintrust” of major filmmakers produced a decade-plus run of classics, including Toy Story, Ratatouille, Finding Nemo, Wall-E, and, yes, The Incredibles: “The services of this cohesive group of talented, battle-hardened veterans were available only to Pixar,” writes Helmer. “They had it cornered.”

The Incredibles, of course, is also the story of a band of ultra-talented, battle-hardened individuals, whose cornered resource—their superpowers—very much corresponds to Pixar’s pool of supertalent in Helmer’s telling. So it’s tempting to expect that the brain trust of Pixar’s own superhero artists would turn The Incredibles into an allegory of the Great Man, The Powerful Genius, the creative mastermind protecting their vision and talents against the dunderheaded rabble. But close as it comes, The Incredibles does not quite grant us Helmer’s tale. Instead, it tells us another tale about cornered resources. It tells us that just as we weaklings in the crowd depend on superheroes to save us, superheroes must depend on us to be weak. It tells us that superheroes keep us weak by denying us technology that could uncorner their superpowers. And it tells us, then, that individual talent is no cornered resource at all.

In what follows, I would like to reread Helmer’s chapter on Pixar to deconstruct the myth of the cornered resource that permeates so much of our story-telling about great artists and great founders. I’ll break this down into four pieces to make the case:

Why the numbers show that Pixar’s supposed “cornered resource” was not a competitive advantage

Why Pixar’s “cornered resource” of talent wasn’t actually a cornered resource at all, but another Helmerian Power: Processing Power

Why Intellectual Property might be considered Pixar’s actual cornered resource—but isn’t a power at all

The one time that talent does matter: when it’s collectivized.

It is hard to tell stories without heroes, after all, and the myth of the cornered resource extends far beyond 7 Powers to reassure us that certain figures have singular traits and talents, forged in the smithy of a script doctor, that simply could not be reproduced. Often, we might note, these stories are used as alibis for the abusive personal behavior of figures like Steve Jobs and John Lasseter—two of the three members of Pixar’s “founding geniuses,” according to Helmer.

Yet for its many missteps, Pixar also shows us how powerful a company can be when it fights the tendency to placate individual genius and instead devises processes for headless, multiplayer creation that gives a role to all workers. In that sense, we might think of Pixar as giving us a template of a future power: uncornering your resources and making their talents available to all levels of the organization.

Unextraordinary Numbers in an Extraordinary Industry

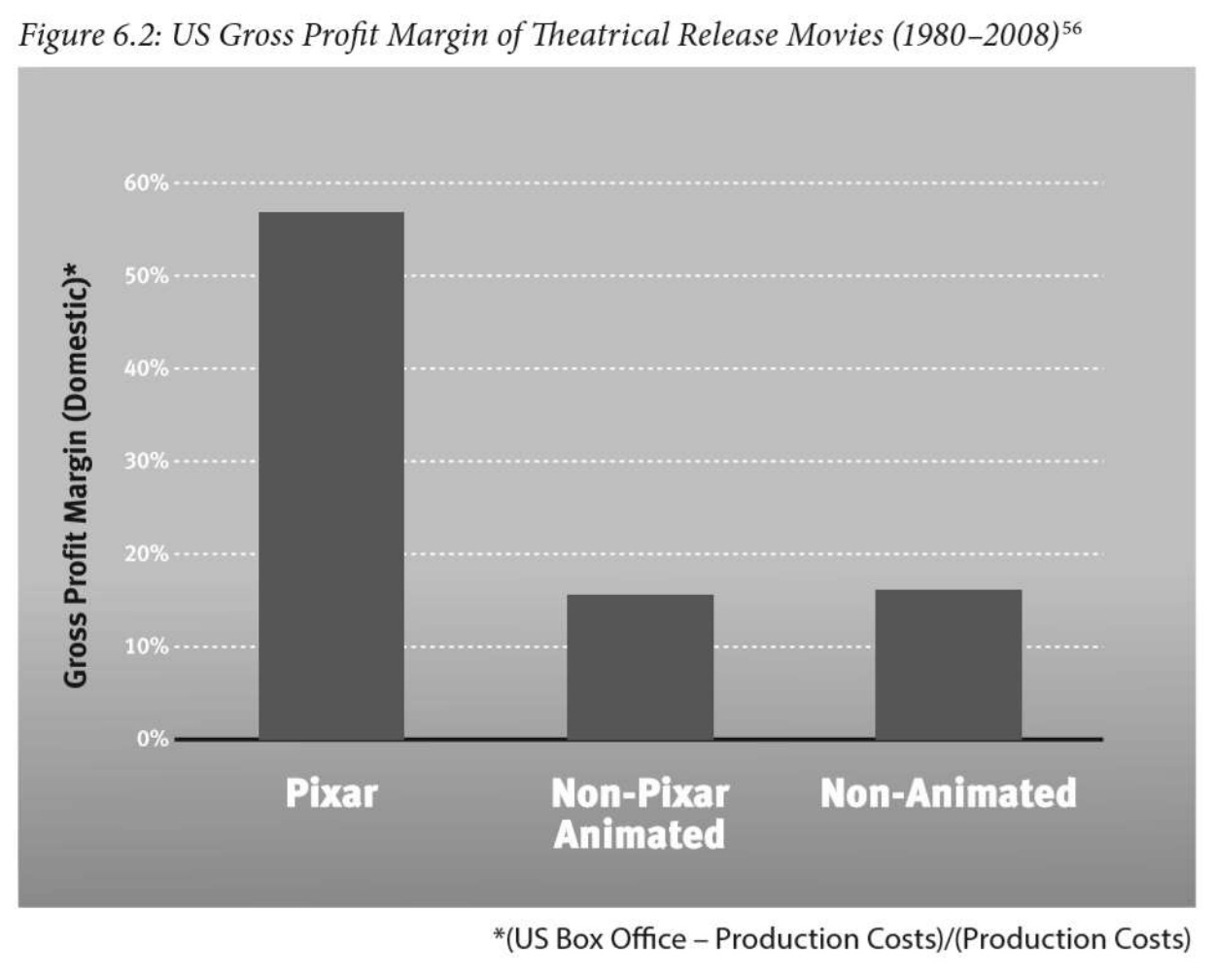

Let’s start with the easiest point against Helmer’s argument: no, Pixar’s cornered resources did not give it extraordinary numbers within its industry. In its first fourteen years of releases, Pixar made ten films with a total budget of $1.04 billion and worldwide profit of $4.68 billion. A nearly 5x return sounds incredible, of course, and Helmer notes that “on average these films achieved a gross profitability nearly four times that of the average of all other theatrical releases or all non-Pixar animated films.” He accompanies the statement with a bar chart showing a soaring column for Pixar that looms victoriously over the stumps that are “non-Pixar animated” films.

But these are extremely misleading metrics. Rather than compare Pixar to all non-Pixar films, Helmer might have compared it to other major 3D animation studios like Dreamworks (the Shrek and Madigascar films), Big Sky (the Ice Age and Rio franchise), or Illumination (Minions and Secret Lives of Pets). And if he had done so, he would have shown that Pixar’s performance has been pretty average. Its domestic gross profit margin on its first ten films was 58%, compared to Dreamworks’ 56% on its first ten films, but there’s no reason to limit ourselves to the US market either. Worldwide, on its first ten films, Pixar had a profit margin of 82% to Dreamworks’ 79% to Blue Sky’s 80% to Illumination’s whopping 89%.

Furthermore, those studios all released their first ten movies in the same or less timespan as Pixar, accelerating their returns. Dreamworks, for example, released its first ten movies in seven years to Pixar’s fourteen, and that pace of production is one of the major reasons that despite forgotten fare like Over the Hedge and Sinbad, Dreamworks returned profits of $7.76 billion in its first fourteen years vs. Pixar’s $4.68 billion. Despite Dreamworks being younger, Pixar and Dreamworks have had almost identical lifetime profits ($11.1 billion), with slightly different playbooks: Pixar generally releases fewer films with higher profit margins (77% over its lifetime) whereas Dreamworks releases many more with lower profit margins (72% over its lifetime). If one had to pick a winner commercially, it would certainly be Dreamworks, whose spray-and-pray strategy positions it to find and milk the next big franchise while making the same amount of money in a shorter amount of time.

But there is also no real need to pick winners. 7 Powers is a wonderful guide to what makes companies defensible against the competition, but it’s arguable that 3D animation studios don’t really have to be that defensible. When each studio has limited resources to release a film or two a year while audiences have the capacity and desire to watch dozens or hundreds, they’re all in a strong position to coexist as long as they tackle different stories that release on different weekends. There is room to say, then, that Pixar is both an extraordinary company on its own terms, as well as a fairly average one in its industry.

Pixar’s True Power: Processing Power

But Pixar is extraordinary on its own terms. And on the surface, there are compelling reasons to buy Helmer’s argument that Pixar’s superheroic core team is what powered the company to become the first major 3D animation studio. Indeed, with little interest in Hollywood or animation, Steve Jobs spent a decade shoveling $50M into an unprofitable computer company in the hopes that its hardware would take off and he wouldn’t have to admit a third defeat after NeXT and Apple ousting. John Lasseter, a former Disney animator with a weird genius for anthropomorphizing lamps and cars, somehow subverted that money into a series of successful animation projects. And Ed Catmull, computer scientist and Pixar cofounder, pioneered digital animation techniques, including texture mapping, subdivision surfaces, and z-buffering, which would allow audiences to believe they were watching a soft-rimmed abstraction of our world as it was filmed in real-time, rather than a mess of splintered pixels or, worse, an uncannily warped reality replication.

Still, it’s arguable that Catmull’s major innovation was not technical but managerial. Catmull spends the bulk of his own account of Pixar, Creativity, Inc., discussing the operations of the Pixar “braintrust,” whose genius is, for Helmer, Pixar’s core “cornered resource.” For Catmull, however, the point of the braintrust isn’t that it’s an assembly of the top talents in the field; as he continually points out, most of Pixar’s major directors had no filmmaking experience and learned on the job. Pixar’s braintrust, writes Helmer, “is largely restricted to a specific set of individuals [and] simple inclusion into the group will not preternaturally endow newbie directors with the ‘Brain Trust process,’” but both Pixar’s own story and Catmull’s own model teach exactly the opposite lesson. “It is better to focus on how a team is performing, not on the talents of the individuals within it,” writes Catmull. Rather than a colloquium of individual geniuses, Pixar’s braintrust is very much a process to produce headless art.

And it is significant that the braintrust is a process, not a result—meaning that it is not a cornered resource at all, but fully replicable from one institution to another. For Catmull, the real test of the braintrust came when he was made president of Disney Animation in 2007 after Pixar’s merger with Disney. Disney was coming off a series of bare-successes and flops, including such non-classics as Teacher’s Pet, Home on the Range, Valiant, The Wild, and Tinker Bell. As Catmull tells it, he decided not to fire key personnel at Disney, but do quite the contrary: give them more options to speak, interact, and share concerns. The result was mega-hits like Tangled and Frozen.

For Catmull, this transplantation of the Pixar braintrust model to Disney animation forced everyone to speak out, take greater autonomy over the project, and think creatively about issues—it was, in short, a way to empower pre-existing talent at all levels of production rather than to give voice to a few select geniuses. “I want to emphasize that it was still populated by most of the same people John and I had first encountered when we arrived,” he writes. “We had applied our principles to a dysfunctional group and had changed them, unleashing their creative potential.”

Put that way, and the braintrust starts to sound suspiciously like another of Helmer’s 7 Powers: Process Power. For Helmer, “Process Power” refers to the ways that a company’s organization, developed over time through every level of its culture, enables a superior product. The ease with which Pixar replicated its own organization at Disney may belie the claim that it really is a unique power at all—and certainly, it might be argued that the relatively greater success of other 3D animation studios undermine that the braintrust was a power at all. But to the extent that Pixar really does produce superior films, it’s likely because process power unleashes talent at every level whereas the argument for cornered resources would assume, naively, that talent were contained to one or two geniuses at the top.

If that seems debatable, we just need to look at Helmer’s example of process power: Toyota, whose superior production methods allowed it to make a better car for cheap. And which company does Catmull repeatedly highlight to explain the power of Pixar braintrust?

Catmull:

“I soon discovered that the Japanese had found a way of making production a creative endeavor that engaged its workers—a completely radical and counterintuitive idea at the time.. The essence was this: the responsibility for finding and fixing problems should be assigned to every employee, from the senior manager to the lowliest person on the production line… They installed a cord that anyone could pull in order to bring production to a halt. Before long, Japanese companies were enjoying unheard-of levels of quality, productivity, and market share… While Toyota was a hierarchical organization, to be sure, it was guided by a democratic central tenet: You don’t have to ask permission to take responsibility.”

For that matter, Catmull even refers to his pep talk to Disney as the “Toyota speech.”

So the braintrust starts to look particularly special as an organizational principle that can convert human creativity into major franchise properties that build a brand—as well as opportunities in sequels and merchandising. To put that in Helmer’s terms, a braintrust converts Process Power into another power, Branding.

But it might be worth asking, then: why not consider Pixar’s characters and technology as its true cornered resource, rather than its individual talents? Perhaps we should say that that is the true moral of the Incredibles’ fighting Syndrome to retain proprietary control of their superpowers, or, to take another example of intellectual property mythologizing itself, Tony Stark’s refusal to manufacture his suits for the citizens he purports to save. The real lesson, we might say, is not that branding or technology is bad, as our opening discussion of The Incredibles would have led us to believe. Rather, these web 2.0 superhero movies teach us another message: technology is fine as long as it belongs to the visionaries who created it—but by no means should be given to the masses for everyday use.

In other words, isn’t intellectual property the real cornered resource?

The Real Cornered Resource: Intellectual Property?

“There is no precedent for this sort of sustained success in the movie business,” Helmer writes in what amounts to an extraordinary distortion of numbers, but if we apply his point to 3D animation studios generally rather than to Pixar in particular, he has a point. Pixar, Dreamworks, and Big Sky really are incomparable to a Warners, MGM, Paramount, or even Netflix (despite Helmer’s attempts to compare them). Whereas traditional Hollywood studios have traditionally churned out hundreds or thousands of hours of content per year, 3D animation studios are able to make one to two mega-films each year, with little room for failure. In classic Hollywood, a figure like John Ford could make seven films in three years, including such mega-classics as Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, The Grapes of Wrath, and How Green Was My Valley (25 Oscar nominations among them), as well as the mostly-forgotten Tobacco Road and Long Voyage Home: if the quality was inconsistent, it could afford to be. Budgets were cheap, shooting times were short, and the possibility of things-going-wrong was high.

3D animation studios, by contrast, need to get everything right. Yet they also have a strong probability of doing so. That’s partly because the writing-and-directing process merge together in animation—directing is really a form of writing pixels onto a computer screen—so that computer animation studios can continually retool their films throughout production in response to audience feedback, as if they were reworking a song.

But the main reason that computer animation has a strong probability of success compared to live-action movies is because it’s continually building off its own intellectual property.

To understand that advantage, it’s helpful to see Pixar, Dreamworks, and Big Sky not only as media studios but tech companies. The differences between these business categories are, traditionally, extreme. In his blow-by-blow account of a decade of Pixar contract negotiations, Pixar’s first CFO Lawrence Levy offers one distinction: “even if a film does just okay in its theatrical release, it may have value for years in a film library. That’s the opposite of tech products that become obsolete quickly.” Hollywood studios, in other words, would traditionally have the advantage of building a long-lasting library of products with decades of ongoing value, but the disadvantage that they would have to make new entries entirely from scratch. Tech companies, by contrast, would traditionally have the disadvantage that their products would go obsolete without any ongoing value, but the advantage that they could update old products with a few tweaks to release new versions, without having to work from scratch.

But because of intellectual property, 3D animation arguably have the advantages of both a Hollywood studio and a tech company. Like a Hollywood studio, animation studios build a backlog of childhood classics that generate income for decades. But like a tech company, each new product is in many ways an update of an older one, building on technological innovations and rendering software whose capacities define those of the movie. The movie itself, of course, must still be written and scored and performed afresh, but its own production is also R&D for future productions, developing new technology for animating physics, places, and faces. That’s doubly true when the technology is used to create characters and sites that can be redeployed in sequels—perhaps one reason the rise of 3D animation has accompanied that of mega-franchises over the past two decades.

So we return to our previous question: doesn’t intellectual property represent the true power of the cornered resource?

And I would argue no, not quite. Intellectual property gives companies advantages, to be sure, but it isn’t a defensible power that can drive consistent differential returns, as Helmer insists cornered resources to be. Characters arguably offer us the strongest case for intellectual property as a power, for example—Mickey Mouse, Buzz Lightyear, and Rocket the Raccoon arguably have longer-lasting box-office power than any human actor—but even characters are only meaningful in the context of craftsmanship. Jaws 4, despite the charisma of its titular lead, was doomed to dud without the framework of writing, direction, and lack of continuity errors to give our shark some much-deserved aura. Even the Avengers themselves were the leftover scraps of Marvel until MCU made them massive figures through a fairly headless creative process similar to Pixar’s own.

So no, intellectual property is an advantage but not a power. Animation studios might be best compared to gaming studios: the intellectual property of cutting-edge technology and franchised characters can only make a product successful if they’re the means rather than the end of viewer engagement, tools in the craftsman’s kit alongside empathetic narrative, telling characterization, and psychological suspense. For that matter, as high-end technology becomes democratized over time, these tools really will be the stuff of The Incredibles’ nightmares, increasingly available to the masses to animate our own stories. But one can just look at the success of lo-fi media over the past decades, from Nintendo to South Park to TikTok, and wonder how necessary IP really is for success.

Of course, when we land back on the so-obvious-it’s-dumb argument that Pixar’s success is due to its craftsmanship, we might seem to concede Helmer’s point that the incredible talent of the filmmakers really is what has made Pixar’s films so special. But there’s a more complicated point. Craftsmanship is very much a replicable power at Pixar because it is a process that can be reiterated, just as Catmull successfully translated it from Pixar to Disney.

In that sense, intellectual property is largely meaningful for the process that created it. And genius itself, then, is not an individual ability, but a replicable creative process constantly at play.

Why Talent Still Matters

Let’s end with one final argument against talent as a cornered resource—that Pixar actually squandered that supposed power entirely.

In many respects, Catmull presents as one of the strongest business leaders in media, more comparable to a figure like Jim Simons of Renaissance Technologies than any Hollywood mogul. Like Simons, Catmull emerged from a technical background where he pioneered major academic discoveries, breakthroughs that would power his own work while giving him the discernment and clout to draw top talent. And like Simons, Catmull’s own background in one of the top academic incubators in the world—Catmull’s colleagues at Utah included the creators of Adobe, Atari, Netscape, and Object-Oriented Programming—taught him the value of recruiting and collaboration. And finally, like Simons, Catmull was able to use these managerial insights to create one of the top firms in his field even while populating it with people who had little-to-no-background in that field whatsoever. Getting people who aren’t trained in the discipline can become, perversely, an asset.

And yet, for all the ostensible power of open decentralization at Pixar, it was also managed by two famously toxic figures. Accounts of Pixar inevitably struggle to highlight the contributions of Steve Jobs beyond his generous funding; in Levy’s account, employees hated having him at the office, where he would aggressively belittle the practitioners of a craft in which he had little interest, while the unfortunately-named Pixar Touch notes that Jobs actively rescinded employees’ stock options in the company after getting into a fight with a Pixar co-founder. Lasseter, meanwhile, that creative genius of Cars and Cars 2, was metooed for repeatedly fondling his female staff and making suggestive comments about them in front of the entire company while instilling a culture of systemic groping, verbal harassment, preferential treatment for men, and denied opportunities for women, who were told to stay away from meetings as men wouldn’t be able to control themselves. Women like Rashida Jones and Brenda Chapman left or were dismissed; Chapman’s dismissal, for what it’s worth, is held up by Helmer as an example of Pixar’s high bar for talent.

But what if Pixar actually were the company that Catmull describes it as being: a creative factory where every worker could have a voice and be heard? We might say that the fact it was the opposite is reason to mistrust Catmull’s model or account at all, of course. Maybe. But what if it had given actual voice to women and underrepresented creators? What if the braintrust really were open to stories and experiences that it not only refused to hear, but denied its audience from hearing too? What if, instead of another Cars entry, Pixar made a film about, I don’t know, animals fighting the destruction of their land by climate crisis?

Perhaps these films would have flopped. Perhaps viewers would have been as little ready to hear new voices as Pixar was. Perhaps they would have submitted to Hollywood virtue signaling, reduced the complexities of struggle to a song, and our lives would be enriched only at the smug comfort that we were watching the right thing. Perhaps.

But I choose to read Pixar’s own great success—its implementation of a creative process that could mint great filmmakers out of inexperienced unknowns—as a sign that these may have succeeded and may have changed the ways movies were made. Perhaps that will still happen. Pixar has told itself a great story, after all, that its individual talents were never cornered resources, that its real strength has come from an assembly of diverse perspectives. Of course, it is a hard story to tell, this story without individual superheroes. So it remains a story that they, like the rest of the world, are still working on writing.

With special thanks to Mario Gabriele, Dan Shipper, and the team at Every.

great piece.