When Multiplayer Went Mainstream

Multiplayer mode has been inevitable for 500 years—but which of the multiple multiplayer modes will win?

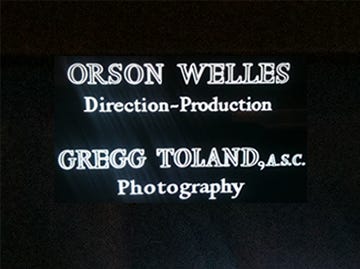

The title card of Citizen Kane, in which Orson Welles famously gives equal weight to the director (himself) and the cinematographer (Gregg Toland)—one of so many Hollywood examples of multiplayer mode.

I.

Within a 24 hour period a couple weeks ago, occasional collaborators Mario Gabriele and Packy McCormick published two pieces on collaboration that they did not, in fact, collaborate on in any way. The pieces concerned what might be termed “multiplayer mode”—that is, a growing cultural trend for creators to work on projects in loose conjunction with one another rather than in the strict hierarchies of Fordist production facilities or in the isolating individualism of post-Fordist freelance life. Multiplayer mode, they argue, is more empowering for creators who get to choose not only their own projects but their own positions in the project, and it generates better results: projects born of all the talent and passion available to the market. Across the pieces, examples include DAOs, NBA superteams, the Avengers, cryptocurrency, the Bible, and Wikipedia.

And yet, in some ways, their visions of multiplayer mode couldn’t be more opposed.

McCormick’s, “The Cooperation Economy,” focuses primarily on the power of the creators, the star solopreneurs who can pit the power of fans against the weaknesses of modern corporations to set their terms for employment. For McCormick, these creators work when it’s worth it, and it’s worth it when they can work with each other. But they maintain, above all, their individuality as irreplicable voices offering the double wares of their fanbase and their talent. “Super Teams” of such workers, he writes, “can be a superior alternative to full-time employment for people who want to retain optionality, flexibility, and individualism while leveraging the benefits of an expanded network, specialization, and community.” In this utopian telling, workers don’t need corporations, but corporations do need workers—or more precisely, the best workers, the ones who set their own terms because they have no substitute. It is a vision of workers as NFTs, most powerful when sold as part of a larger collection.

In Gabriele’s telling of “Multiplayer Media,” however, the unique talents of the creators dissipate into those of their fans and eventually the work itself. Gabriele’s vision here is somewhat similar to the one I wrote about in “Fan Fiction and the Consumer-as-Creator”—fans actively shape and release their favorite creators’ work themselves through feedback, active involvement, forks, and distribution, until they themselves become the creators—but significantly expanded. For when the work of fans merges with the work of the creators they love, what matters is no longer the individual voice of a diva but the choral harmonies of an ensemble. Multiplayer mode, here, is more akin to crowd-sourced artistry, recalling something like Orson Welles’ description of Chartres: “The premier work of man… this anonymous glory… without signature.” It is, in Gabriele’s words, “headless,” a confluence of overlapping labor. As Welles put it, “Maybe a man’s name doesn’t matter all that much.” Here, the author is more like a token burned during a transaction.

So if you prefer to follow McCormick’s analogy, Super Teams are The Avengers, the superheroes. But Multiplayer Media of the sort that Gabriele describes is more like The Avengers, the movie itself—made largely by faceless technicians. McCormick’s Super Teams are consumer-facing, in other words, the proverbial creators of the creator economy. Gabriele’s, by contrast, are behind-the-scenes, the engineers of open-source projects.

It is notable, above all, that these two paradigms are not mutually exclusive. Just as the creator economy extols the superhuman feats of haloed individuals in direct-to-consumer brands, open source extols the anonymous work of the masses in enterprise software. The actor and the screenwriter; the influencer and the engineer. At some point, both are likely to feed off each other, developers turning into creator-stars, and creators turning into anonymous engineers—one version of collaboration that’s aspirational and individualist, the other all-too-accessible and communal. Each is, perhaps, a harbinger of things to come.

And each was also, I think, inevitable.

II.

The old money, fluent in oil paintings and horseless carriages, frets over aperitifs about the impact on real estate prices of a new-fangled technology—the automobile. It is around the turn of the century, partway through Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons, and a group of esteemed city elders is concerned that this devilish contraption, the car, might disrupt the time-space continuum of capitalism in the early 20th century. “Our real-estate values here in the old residence part of town would be stretched pretty thin,” says one mustachioed patriarch upon hearing that the car could enable easy commutes to the suburbs. But the car-maker at the dinner, Eugene, sees even graver spiritual implications.

“With all their speed forward they may be a step backward in civilization. Maybe that they won't add to the beauty of the world or the life of the men's souls, I'm not sure. But automobiles have come and almost all outward things will be different because of what they bring. They're going to alter war and they're going to alter peace. And I think men's minds are going to be changed in subtle ways because of automobiles.”

For all the (correct) talk of irrevocable change, the discourse could just as easily be applied to the railroad—or the internet. As David Harvey wrote in 1969, quoting Marx, “Expansion occurs in a context where transformations in the cost, speed, continuity and efficiency of movement over space alter ‘the relative distances of places of production from the larger markets’. This entails ‘the demise of old centres of production and the emergence of new ones.’” What was true for the railroad was true for newspapers, cars, planes, radios, and Reddit: a technology allows people to move farther and farther away from each other physically, precisely because it connects them more closely as an “imagined community” with access to each other’s thoughts and opportunities.

To an outside observer, humans become more and more isolated from our tribe over time. But it is only because we are more and more connected with others in communities of our own creation.

Online, we enjoy a collective illusion that we are beholden only to the worlds we’ve chosen to join, the tribes we’ve chosen to defend, the games we’ve chosen to play. It is this half-illusion of choice that defines the success of so many of the technologies above. Those of us in the creative classes get to pick our world to live in (the West or the East? The suburbs or the city?), but even as the technology gives us greater access and mobility, it upends a network of physical relationships and contingencies for the poorest and the rich—who often find themselves irrevocably tied to a fallen order.

The simpler name for picking and creating our own tribe is, simply, multiplayer mode.

III.

It is tempting to draw a history of multiplayer mode back to Greek forums or, more recently, the printing press—decentralizing power away from papal authority and into the hands of any literate Northern European who could now access The Good Book on their own time, in their own space, without walking to church. (A similar shift, in a strange way, to the move from cinemas to TV some centuries later.) Politically speaking, multiplayer mode is often synonymous with leftist collectives that sprout up in times of populism: the Paris commune, the WPA projects of the New Deal, the cinema collectives of post-68 France and Japan, Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring. For whatever it’s worth, Welles’ late-career concerns about the erasure of artists’ signatures through the collective work they produce makes sense in this context as well: he was a product of the New Deal, which not only funded his early theater projects but enabled him to collaborate on collectivist and committedly leftist visions of Haitian independence (Macbeth) and a history of jazz (a joint project with Duke Ellington that never happened).

The fact that multiplayer mode today, however, has very little to do with leftism and has instead become something of a corporate standard for user-generated online universes in Roblox, TikTok, Twitter, Crypto, and Github, raises what’s perhaps a more interesting question. How has multiplayer mode changed and developed over time?

One easy way to understand the shift is to take Carlota Perez’s seminal chart illustrating the five eras of technological development—or, more precisely, to take it out of context.

What if we renamed the 3rd age as the age of the telegraph and the 4th age as the age of cinema? We might start to see three patterns:

Each age finds ways to close the relative distances of time and space in bringing humans into closer contact, communication, and community—enabling not only new forms of collectivization but the growing power of consumers and fans in giving feedback to centralized collectors and creators. At the same time, we move into greater and greater isolation physically, from theaters and cinemas (spaces with strangers) to radio and TV (spaces with family) to computers and mobile phones (spaces on our own).

Our relationship with time changes as well: we shift from taking weeks to coordinate with other parts of the world (industrial revolution) to expecting daily updates (newspaper), live updates (radio and TV), and live updates with anyone anywhere (texting and internet and live gaming).

This represents the precondition for multiplayer mode: more and more people can join in to communicate with one another in detachment from their physical world, and they can do so more and more easily as well. For each moment that we become less interactive with our immediate surroundings, we become more interactive in our imagined world of media.Each age creates a new good or service that the next will find a way to propagate. The industrial revolution creates goods that railroads need to distribute; the railroads create supply chains that telegraphs need to coordinate; telegraphs create news empires that new media will best disseminate; new media creates virtual worlds that the internet is best positioned to distribute. This represents the expansion of multiplayer mode from supply chains to consumerism, from centralization to decentralization. Connectedness itself is democratized.

Technology has gradually shifted from the material to the abstract—from physical goods to information. This, too, is democratizing in its way: we can’t all access or shape steel, but we can spout and relay facts and opinions. Just as significantly, it means that revolutions are increasingly mental, reshaping our relationship to space as we connect to each remotely, without necessarily changing the physical land itself. (In an era of climate disaster, let’s hope, at least, this is true.)

New revolutions no longer transform the world we live in physically but offer an alternative to it. As Perez notes, transformative technologies don’t just solve an immediate problem but create a platform for entire new experiences, well beyond their intended purpose; the greatest market is never for technologies that solve long-standing problems, but technologies that generate new experiences. It’s this move that brings multiplayer mode into the mainstream—the hierarchical worlds of the family, workplace, and school dissolve as standards for how we identify ourselves. Over time, it becomes the norm to see ourselves in the worlds we choose to join.

IV.

The Magnificent Ambersons ends in the shadow of tenement housing, city-edge factories, and anonymous warehouses—the tools of mass-manufacturing that look, themselves, to be mass-manufactured. In more ways than one, they are the heir to the automobile and the assembly line that created it.

We might note another trend in Perez’s chart, then: each revolution helps hide the failure of the previous order, which is just another way of saying that each revolution fails. The major technologies we mentioned above are self-replicating, after all, laying infrastructure for services that demand more infrastructure in turn—until the marginal benefit is close to 0. At some point it stops paying to lay more track or build more roads, and if a crisis doesn’t ensue, that’s likely thanks to the bubble of new technologies offering new paths to economic growth. The only permanent victors, then, are the financiers who find new revolutions into which they can funnel their capital. Each technological revolution, in other words, just ends up consolidating the same kind of hierarchy it was meant to disrupt.

As Harvey wrote:

“Capitalist development has to negotiate a knife-edge path between preserving the values of past capital investments embodied in the land and destroying them in order to open up fresh geographical space for accumulation. A perpetual struggle ensues in which physical landscapes appropriate to capitalism’s requirements are produced at a particular moment in time only to be disrupted and destroyed, usually in the course of a crisis, at a subsequent point in time.”

As Harvey suggests, the rise of multiplayer mode may break down centralized financial powers who have hoarded capital for so long through control over physical land. As a product of democratized online organizations, multiplayer mode may even lead to greater democratization by increasing access to goods and information to anyone who needs them. But it is unlikely to be democratizing financially; more likely, it will raise a few middle-class technologists to the upper brackets of capital, generating a new hierarchy of wealth as technological revolutions generally do. It is fashionable, after all, to talk about the ways that we can get rich by leveling the financial playing field, so long as we don’t think too deeply about the inherent contradiction in what we’re saying.

McCormick’s piece is particularly revealing here, with its continual focus on the “best” creators leveraging their power for better terms. The democratization of power and finance plays into all our ideals of the American dream: in theory, anyone can make it, but in actuality, only the best actually will. It is thrilling, of course, to think that they have a shot. But finance is often a zero-sum game—one person’s winning buy is another’s losing sell—and the fact that everyone has equal access to succeed in a decentralized retail market doesn’t mean that those without education, expertise, proprietary insight, or billions of dollars in holdings have equal chance or expected outcomes. Multiplayer mode may be democratizing in enabling user-generated finance, but it will only be empowering if it gives people the resource and access to good teams. Whether that can happen remains one of the most important questions of our current technological revolution. I don’t know that there are great answers.

V.

Within the same 24 hour period that McCormick and Gabriele published their pieces on multiplayer mode, Alex Danco published his own, “Civic LARPing,” with a quite different twist. Danco’s multiplayer world, unlike McCormick and Gabriele’s, is not open to users to set the terms of their work and participation: instead, it’s ruled over by a D&D dungeon master who sets the rules of the game. “The art of building compelling worlds is: can you create a world that other people can step into, explore, and find challenges for themselves inside it? That’s the critical part,” he writes. “Give people the starting material to go LARPing; they won’t disappoint you.” The rules are something like a writing prompt—representing both the inspiration and limitations of the performances that participants can enact.

As Gabriele notes in his own piece, many of the most successful user-generated platforms were founded on limitations of the medium: “Twitter restricts the storyteller to 280 characters; Facebook rewards short, high-emotion commentary; Instagram, Snap, and TikTok prioritize brief clips.” These are, in a way, the rules of Danco’s game. The creator here is not quite empowered to self-expression as in McCormick nor dissolved anonymously into the work itself as in Gabriele, but instead is always performing a role that both is and isn’t themselves, that they both have and haven’t devised. We could be describing ecclesiastical ceremonies from 500 years ago, or we could be describing selfies and subtweets. Our own identities become the product of multiplayer mode—they are a collaboration between ourselves and our community that we perform together through rites and rituals.

And when we talk about “democratization”—of finance and investing, of education and information, of political participation—we are, so often, talking about Danco’s LARPing, excited masses aping into new positions at the urging of the crowd, taking a “position” in a stock or political platform because it’s a token of self-identification with a tribe. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Financial and political markets not only offer stages for personalities to perform but actually “perform” themselves according to the mandates of their participants—so taking a role in a crowd may, in fact, be one of the best ways to have impact. But civic LARPing also means performing according to the rules and standards that have been normalized over time. It might be democratic that everyone gets to join the game (though even that’s debatable), but that doesn’t mean the game’s rules give equal opportunity to all. Multiplayer mode can only be democratic if the game itself is.

We can end here with Welles, who spent his last years attempting to make a true LARPing multiplayer movie, The Other Side of the Wind: distributing the cameras to the actors, he asked them to improvise, occasionally from dungeon-master-like prompts, letting them take not only their performances but the film itself into their own literal hands. “I want to make a film that is not a film by Orson Welles,” he said. “The film is a mask.” For all its feints of raw, documentary realism, it is a film, like all of Welles’, about performance—about the ways that dinner party guests exaggerate stories and gestures for each other’s benefits, about the ways that comedians do impersonations to draw attention to and from themselves at once, and about the ways that men put on masks of machismo to paper over their fears. In other words, it’s about the characters we become when we’re constantly being filmed for consumption, which is to say, it’s about a world of social media—the world that Welles himself felt he inhabited and that the rest of us all populate now.

In a way, the product of multiplayer mode in Other Side of the Wind is paranoia, failure, and insecurity: the actors quickly resort to the most gender and class-based stereotypes of how they think they should act, desperately entrenching social norms for the sake of validation, forgoing the chance to perform however they like. The film itself, however, is a testament to another vision of multiplayer mode—as emancipatory, open-ended, and forever evolving. Freely matching and mixing discontinuous shots from the time of production to tell a coherent narrative, it often offers a roadmap for many other movies that might have been, and it is perhaps a feature, rather than a bug, that in well over a decade, Welles never finished his open-sourced movie. Open-source projects, after all, are defined by their ability to keep evolving.

This might be one last way to think of the different visions of multiplayer mode. For McCormick, there is a clear end and objective in sight—a goal that stars come together to achieve. For Danco, there is only endless reiteration with slight variation of unending ceremonies humans choose to perform. For Gabriele, however, headless projects simply mean endless evolution, much as James C. Scott described cities and languages: “Despite the attempts by urban planners toward designing and stabilizing the city, it escapes their grasp; it is always being invented and inflected by its inhabitants.

For both a large city and a rich language, this openness, plasticity, and diversity allow them to serve an endless variety of purposes—many of which have yet to be conceived.”

With special thanks to Lila Shroff.

While multiplayer mode presents a challenge to traditional financial and capital allocation systems, and increases access to goods, how does it realize true value in both a traditional and new sense? Is traditional value creation over, and what replaces it? There is the notion that capital allocated to ideas and their progenitors, but this likely can't happen with some norms and rulemaking.