Visualizing Decentralization

What if we never had decentralization because we misunderstood what it would look like? And what if what it looks like—is many, many things?

I.

One problem of visualizing decentralization is that our models for it historically come from those who have detested it. In a sense, attacks on decentralization begin as early as the Greeks, with a charge leveled by Heroditus and Plato—that democracy fails because hucksters inevitably rise to exploit the ignorant masses.

In a sense, it is an argument that survives today, even among cryptocurrency adherents. As Bitcoin’s price finds itself hijacked by Jekyll-Hyde maneuvers of the occasional richest man in the world and his evident archnemesis, well, it’s hard not to be sympathetic to the arguments of Greeks that left to our own devices, we are not very good at electing our own Gods.

Still, the first step to undermining this argument is to visualize it. In both Plato’s Republic and Herodotus' Histories, an upstart philosopher makes the mistake of arguing that democracy will empower the masses by giving them liberty. No longer will humanity be subjected to a ruler, as they would in tyranny.

Now, instead, they will elect their own rulers.

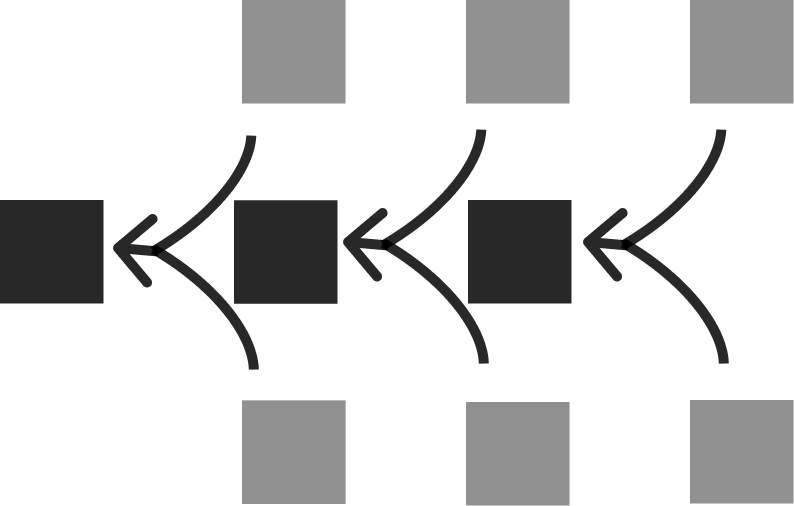

It is, above all, a difference of vectors.

“Offices of state are exercised by lot, and the magistrates are compelled to render account of their action: and finally all matters of deliberation are referred to the public assembly,” explains the democratic ideologue in Heroditus; democracy, says Socrates in the Republic, “comes into being when the poor, winning the victory, grant the rest of the citizens an equal share in both citizenship and offices—and for the most part these offices are assigned by lot.”

This argument turns out to lay the terms for its own undoing. Rather than argue against democratic principles of liberty and freedom, Herodotus and Plato embrace them—in order to claim that they are the first casualties of democracy itself. “Whence arose the liberty which we possess?” asks Darius, Herodotus’ thoughtful champion of tyranny. He answers clearly: from the despot who maintains an orderly state. Certainly, he clarifies, liberty does not arise from the people, who begin to cluster in backroom cabals where “there arise among the corrupt men not enmities but strong ties of friendship: for they who are acting corruptly to the injury of the commonwealth put their heads together secretly to do so.” The problem with democracy isn’t simply that it offers freedom, but that it fails to protect it.

Democracy, paradoxically, is not democratic at all, but turns out to be an awful kind of tyranny—a tyranny of chiselers, of the corrupt sort who are able to connive the dumb masses into giving them power in the first place. Plato’s more extensive argument against democracy also reverts to this point. Democracy empowers two types of unsavory and “spendthrift” citizens, “the most enterprising and vigorous portion being leaders and the less manly spirits followers.” In other words, democracy empowers a ruling class that gruesomely “makes speeches and transacts business” to exploit sheep-like followers, and just as horribly, it empowers the sheep-like followers to elect their own exploitation, as they “swarm and settle about the speaker's stand and keeps up a buzzing.”

Listen carefully, and you can hear Plato attacking early capitalism: suave salesmen peddling snake oil, working crowds into a frenzy, feeding on the masses’ social and financial capital to enrich their own. Indeed, it is hard not to see that story playing out on something like Twitter, a kind of democracy-turned-tyranny, in which followers turn into worshipers for those who thrive off their attention and command the space (and stock market) in turn.

And so, the diagram looks much the same as before, but the vectors open themselves to a more cynical reading, suggesting the ways that swindlers suck power from the masses for their own despotic gain.

But what if we pause and say that there’s a deeper issue here—that only the vectors have changed, while the underlying structure has remained the same?

Indeed, Plato and Herodotus’s assumption that the body politic will inevitably revert to a hierarchy turns out to be a kind of foundational myth for centuries of political thought. When the social contract theorists—Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau—describe the various ways that citizens give up their rights to a sovereign to rule them in turn, they’re effectively describing a sequence in which people unite to create a bottom-up hierarchy for the sole purpose of devising a top-bottom hierarchy.

But what if there were a structure that could maintain its own decentralization?

In fact, late in the 20th century, two political philosophers would propose another model entirely, nearly an anti-model resistant to fixed-state imaging. They, too, sensed that all traditional forms of government maintained the same system with different vectors. And in A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari propose their own decentralized alternative: “the rhizome.”

“In contrast to centered (even polycentric) systems with hierarchical modes of communication and pre-established paths, the rhizome is an acentered, non-hierarchical, non-signifying system without a General and without an organizing memory or central automation, defined solely by a circulation of states… A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interning, intermezzo… unlike trees or their roots, the rhizome connects any point to any other point, and its traits are not necessarily linked to traits of the same nature; it brings into play very different regimes of signs.”

Part of what defines the rhizome is that it can’t be defined because it is a movement, a flux, a flow between bodies tracing the interplay between them in a constant state (or non-state) of becoming. That also makes it hard to visualize. So to understand the rhizome, it becomes tempting to find a non-visual analog instead, like Borges’ library or the internet itself. Wikipedia, for example, might arguably be a rhizome, an endless series of links each leading to the next, shifting over time, documenting its own shifting state. But even that analogy leaves aside the ways that varying states within a rhizome connect and inflect each other, shaping one another in real-time like a kind of atmosphere.

Likewise, blockchains are something like rhizomes, continuously flowing records of person-to-person transactions, effectively allowing any point to connect to any other point, serving as the medium or the middle-ground between users. But once a blockchain has verified a historical transaction, it is an immutable “organizing memory,” and rather than bring into play different types of signs, it usually translates each action into a legible financial code.

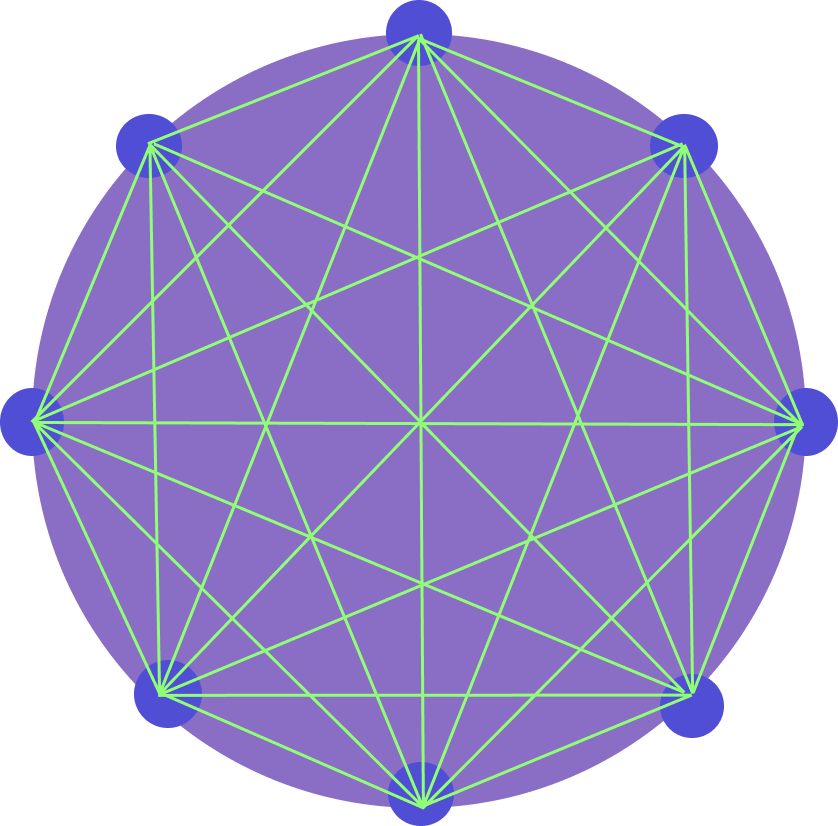

Other distributed ledger technologies (DLT) offer even greater opportunities for rhizomatic decentralization, then, in not requiring chronological sequencing at all. Hedera Hashgraph, for example, uses a “gossip” protocol, for example, while Radix interweaves different shards together as “multiple concurrent timelines” that only need refer to each other for related events. Imagine multiple parallel universes that allow portaling between worlds, and you’ll have something like Radix, which could effectively enable different blockchains to become interoperable.

This diagram for achieving consensus on Radix, adapted from its whitepaper, gives us a strong contender for rhizomatic decentralization: each shard is a row without beginning or end that is also positioned in the middle of multiple other shards, all connecting, never needing to verify an entire memory of the system as a whole but instead interconnecting at any point.

But even these images are limited suggestions of what a larger network, speaking in multiple languages, would actually look like. A Thousand Plateaus, though illustrated, features no visualization of the rhizome—as if still images couldn’t possibly visualize what they have in mind. Instead, we might resort to moving images to picture how a rhizome develops through time. If we follow our black-box logic of classical political bodies, the rhizome might resemble something like a Hans Richter film, a black box in a white box dissolving into a white box in black.

II.

A week ago, my friend and occasional cowriter Annika Lewis published a wonderful piece entitled “Decentralization is not a Binary,” which proposes the ways we might track all historical governance systems as absorbing different features of centralization and decentralization or landing at various points on a decentralization spectrum—various points, that is, except the poles. Annika was partially inspired by a podcast James Wang and I did on DAO-ish systems, and this piece, in turn, is entirely inspired by hers.

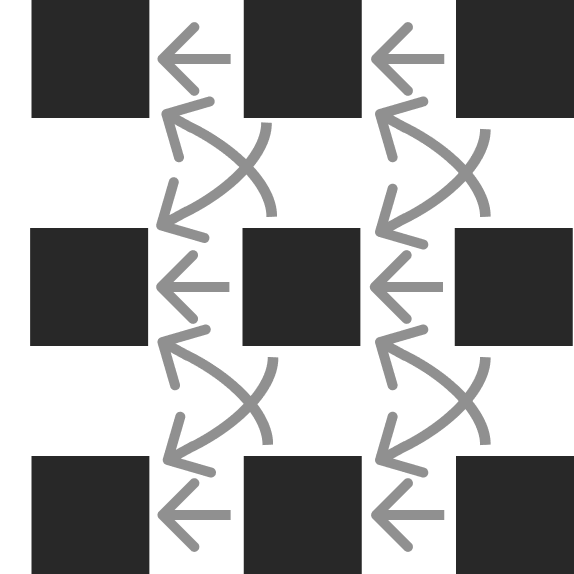

Because what I’m wondering is this: what if we don’t stop at a single-axis spectrum but position decentralization in a two-dimensional graph? On one axis, we could chart decentralization → centralization, but what would we want for the other axis? And how could that inflect the ways we might visualize decentralization?

For example, let’s say that we set our other axis to cover the spectrum between interconnected protocols, in which each node is capable of interacting with multiple other nodes, and sequential protocols, in which each node takes in single actions (or transactions) and then passes it to the next. Centralized, meanwhile, means the actions converge towards a central node that can be managed and controlled, whereas decentralized means that any nodes can come together to contribute to the protocol with equal say—and that their behaviors may not be overwritten by any central authority.

We might get something like this.

Let’s try to understand this by starting with the simplest protocol: centralized and sequential.

In Web 1.0 terms, this is the protocol of writing a document on MS Word, emailing it to a collaborator to edit, and the collaborator’s emailing it to a boss or teacher as the final recipient. In political terms, it represents a sovereign sending down orders to the workers. Each node must pass on the previous node’s instructions, so the protocol is sequential; a boss stands at the start or end of the chain to manage or receive information from the nodes, so the protocol is centralized.

Move up, however, and we move into some of the glories of cloud architecture.

Now we’ve enabled multiplayer media. Instead of passing on a Word doc, users can all collaborate within Google docs; instead of storing information on our own servers, they can use AWS or Dropbox; and instead of doing what the teacher says, the class can set new rules. That the protocol is interactive is clear enough: it is determined collaboratively through the shared inputs of users and will evolve over time. But it is still centralized. Users can only interact with each other in altering one another’s work in a protocol owned by an outside state (Amazon, the teacher); they can not alter the protocol itself.

In this reading, the blockchain will have to risk a trade-off—to be decentralized at the expense of returning to sequentiality.

Here we see a simple visualization of the blockchain in which any parties can come together with equal power to transact together, and the blockchain keeps a sequential record (a ledger) of all transactions. Compare to the cloud architecture above, and we’ll see three major advances in the move to decentralization. First, multiple projects of different and unrelated users all coexist in the same protocol; rather than rewrite each other’s work, users contribute their own side-by-side, something akin to the rhizome’s “very different regimes of signs.” Second, anyone can participate with equal say and control. And third, and most importantly, the protocol itself can be forked and written by its users—in some sense, the workers own the means of production.

The catch, however, is that the ledger is strictly sequential, a single shard that can only verify one transaction at a time with limited capacity for connecting nodes or users to each other. Though we allow p2p remittances between anyone, anywhere, we’ve effectively given up multiplayer media beyond the simplest transactions.

That catch is why Ethereum 1.0 is looking to move to a multi-sharded Ethereum 2.0 and why Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) looks likely, long-term, to surpass the blockchain.

Returning to our earlier visualization, we can see that DLT doesn’t simply increase throughput but allows entirely different protocols to interopreate with each other—enabling each node to be a recipient and transmitter of information as well as an active contributor. One of Deleuze and Guattari’s analogs for the rhizome is an infection, moving between our host bodies and reminding us that for all our vainglorious sense of selfhood, we live our lives largely as transmitters of information, genes, and disease, nodes in a larger ecosystem. That’s one way to understand DLT.

Personally, however, I’d prefer to think of other kinds of cross-species interactions in understanding what a diagram like the one might mean. For example, we might imagine one row (shard) of humans and one of dogs, often interacting with each other on an individual basis and reshaping each other’s sense of self, before rejoining the pack. Or, more simply, we might imagine a p2p education network in which students from each subject can work with each other to teach and learn simultaneously while developing their field in turn.

In any case, these simple axes can give us a simple history of the web, at the very least, if not politics more broadly. And in some sense, the same is true if we choose another pair of axes altogether.

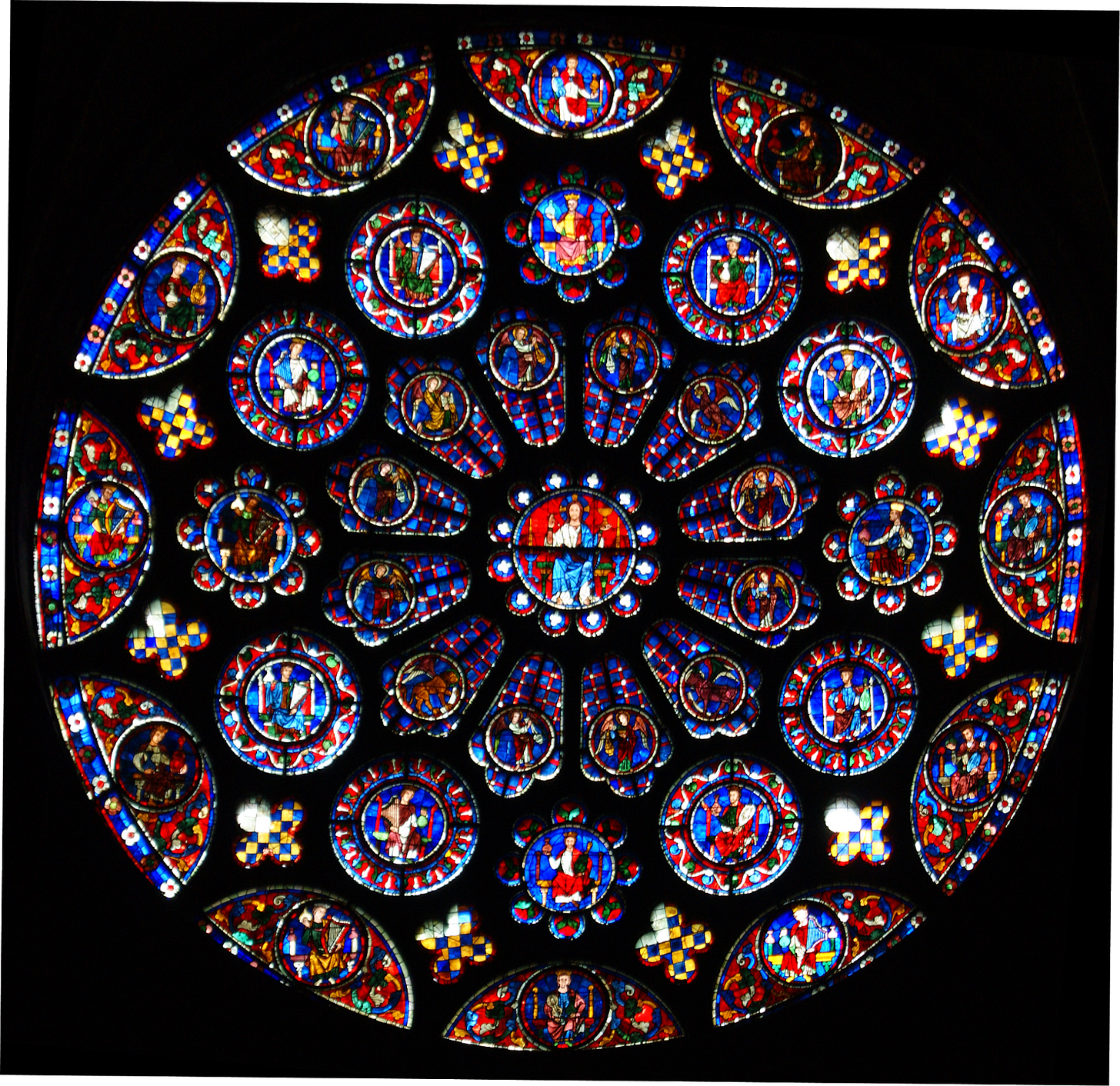

Here, we’ve replaced our vertical axis with a “Monistic → Pluralistic” spectrum, which means we’ve replaced sequential shards with spheres of influence—subcommunities of larger continents in which information and ideals disperse freely. Monistic means that there is a unified whole that each sphere contributes to; pluralistic signifies that each sphere operates independently to create a heterogeneous terrain of cross-cultural interchange.

Again, our simplest regime is in the lower right.

Monistic and centralized, this regime is really just a radial version of the top-down tyrannies propounded by Herodotus and Plato: a central autocrat rules over all departments, bidding them to perform the kingdom’s will. Unsurprisingly, this diagram ends up looking a lot like traditional Christian depictions of a sun-like God beaming his light to the people. Compare, for example, to the radiant visualization of theocracy in the North Rose Window at Chartres:

Harder to parse, however, is pluralistic centralization—what does it mean for independently operational spheres to be centralized?

Pluralistic centralization looks, in fact, a lot like the world of nation-states today—or, if you prefer, the different states of the United States or different families praying to the same God. In a sense, we’ve moved again from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0, where anyone can network with each other under a shared corporate authority. A multiplicity of cultural spheres overlap and influence one each other locally, but they operate under the same sovereign protocol: the US Dollar, the IMF, Apple, Amazon, and Jesus Christ Our Lord.

Next, decentralized and monistic draws us an initial picture of DAOs, p2p democracy—Occupy Wall Street or the Arab Spring—and an open internet.

If this visualization looks centralized, imagine that it is tracing the surface of half-a-globe, converging nowhere, connecting all. At the same time, however, all spheres are unified in a shared lattice with one another. It is a constellation, less than a system, enabling complete interconnectedness as long as one subsumes oneself to the network.

And finally, perhaps most simply, is a model for pluralistic decentralization.

It is a model that doesn’t seem to pertain to the web or states at all, better understood, perhaps, as flocks of birds or whales that share their songs with one another as these slowly disperse across communities. In a way, this is what the analog and natural world can feel like to us: that we live within one community that occasionally intersects, transacts, and trades with others around us.

A digital world complicates things, then, as our communities can now connect not only to our neighbors but to others around the world; still, such cultural interchange remains pluralistic and, in a world of user-generated content, increasingly decentralized as well. So we might re-visualize this depiction of our cultural to show both the local overlaps between spheres in the analog world and the wider connections in the digital one.

This, too, could be a portrait of Web 3.0 or a whole new ecological politics—a constellation of microcommunities with their own rituals and traditions that can all intersect and trade as needed.

It is not so far, in that sense, from the nomadic cultures of hunters and gatherers.

III.

In the human world, decentralization has historically been hard to come by. If we think of Twitter and Facebook not only as casino-like games, as Packy McCormick proposed last month, but political systems, we can see how quickly we humans revert to status-seeking rituals to build cache and power within communities, no matter how decentralized these communities are themselves.

What has changed is that all of us are followers now, quite literally, but still only a few can scale the status ladder to have influence—to become influencers. Ultimately, we are the close cousins of the macaque monkeys, who jockey for social standing by developing coalitions through intimate relationships. The fact that most of us feel our lives to be fairly decentralized, building relationships as their own end, doesn’t alter the way that we’re often helping the more ambitious to gain power; for those that we “follow,” relationship-building may often be a means instead, a way to win the game as central figures.

“Are not all modern States isomorphic,” ask Deleuze and Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus, “to the point that the difference between democratic, totalitarian, liberal, and tyrannical States depends only on concrete variables, and on the worldwide distribution of those variables?” We need new structures, in other words, to circumvent the human tendency toward centralization.

And in a way, the web—or Web 3.0—seems to offer these. DLT, the metaverse, and future multiplayer media all offer possibilities for greater p2p interconnections spanning the globe without any central authority. We are moving towards protocols, not platforms.

But if we look carefully, it is not hard to find successful examples of decentralization all around us. Deleuze and Guattari repeatedly contrast the rhizome with the Tree—a hierarchical structure with an end-state born out of a seed—but as botanists recently discovered, trees socialize through a network of fungi. Fungi offer one of the clearest rhizomatic models, forever growing horizontally and interweaving not only with each other, but with various animals whose bodies they commandeer, each becoming the other. As Francis Gooding suggested recently, the effect of our minds on shrooms is itself fungi-like, rhizomatic: thoughts and senses from all regions of the brain interacting, interconnecting, inter-becoming.

And then there is the lattice-work of chemical polyhedrons, like this “crystal structure of metal-organic composed of Cu(II) and 5-Bromo-1, 3-benzenedicarboxylate” from Meissler’s Inorganic Chemistry:

Finally, we might admit that even the post-nomadic world of humans will offer its own occasional examples of decentralization. Stand in the Mosque of Cordoba, for example, and it can be impossible to find any orientation amidst an outcropping of hundreds of columns and double-tiered arches.

This is deliberate. Unlike Christian churches, which orient visitors in rectilinear submission to a central authority at the altarpiece, mosques feature mihrabs in the direction of Mecca but otherwise open freely, even diffusely, with a very different conception of God. The suffusion of natural light in the Mosque of Cordoba is especially stunning for those of us who grew up in prostration to an authoritarian Judeochristian deity; the light here is not transformed by stained glass to signal a transcendent commander, communicating to us with light from on high, but radiates outward from all directions as if lit from within, without any central source. This light is everywhere and nowhere, all-encompassing by circulating infinitely through the space. It is the light, in a sense, of a God we can sense but never see, an altogether decentralized deity.

As architecture, it is a premonition, perhaps, of things to come.

The Aristophanes comedy `The Birds` is another great example of the Greeks being big time non-beleivers in Decentralization because of `human`nature.

The allegory of the Coding Cave seems appropriate to link on this highly philosophical inspired angle on decentralization: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zx2BCV1-uJk

Very impressive write-up, will take me some rereads to digest well :')

Most impactful philosopher on your life so far?